When Your Personal Trauma Rears its Ugly Head

Babel is not a horror movie but it hits way too close to home

My daughter disappeared when she was 18 months old.

It was an autumn in Saturday. We took the kids—both of whom were still in the “I can’t control my bodily functions” phase—to Crossroads Village & Huckleberry Railroad, a quant, turn-of-the-century village where you can ride locomotives and eat candied almonds.

The big draw was Thomas the Tank Engine.

My son was a huge fan. He watched the TV show religiously, which meant that I, too, watched a lot of Thomas. It’s one of nature’s cruel tricks that he eventually forgot all about it, and 15 years later I’m still quoting Sir Topham Hatt.

The day started well. We boarded the train and watched the countryside roll past. Despite my misgivings, my son was adamant that Thomas was a really useful engine. Like, the most useful.

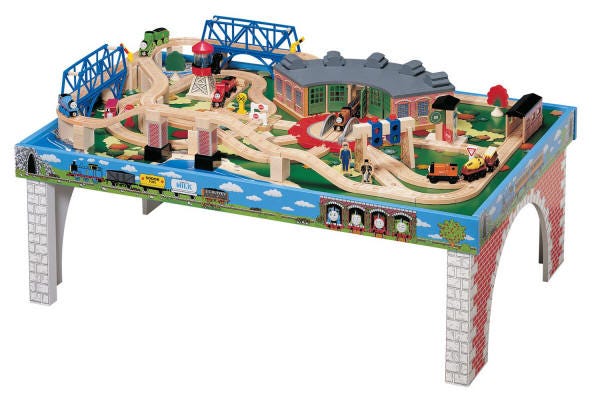

After disembarking, we entered a pavilion where kids could pester their parents for merch and toys that just happened to be artfully laid out. There was a train table at the center. If you’ve never lived the Thomas Life, a train table is a bit of furniture upon which a kid can build their own railroad tracks and towns and dreams.1

All the kids converged upon the table. My son was in the midst, jockeying for any train other than the nightmarish Diesel 10. My wife and I stood chatting nearby and keeping an eye on him. Our daughter, who’s always preferred things that come in pink and don’t involve elbows, loitered around our legs.

And then she was gone.

When people say, “I just looked away for a second,” they mean it. She was right there, and then she wasn’t.

We checked the kids at the table. Fanned out around the pavilion. Reconvened in the middle.

“She’s not here.”

“Where is she?”

“She’s gotta be right here.”

We looked again with increasing desperation. Something horrible lurked at the back of my mind but I couldn’t face it.

There were dozens of adults standing around, surely someone had seen something.

“Excuse me—my daughter is gone. Have you seen her?”

“Sorry, no.” They went back to their hot cider and inane discussions, oblivious to the fact that my world had just ended.

A few asked what she looked like, what she was wearing. That’s where their help began and ended—more questions, ones I suddenly struggled to answer. “Uh, she has brown hair and, uh, I think she’s wearing a pink coat.” Was it the pink coat? Did she have a hat on?

I turned away from the questions nakedly visible in their eyes. How could you lose your daughter? Weren’t you watching her? What kind of parents are you?

I cut the line of people waiting to buy stuff and leaned toward the middle-aged woman running the tent. “My daughter is missing.” The subtext was blindingly clear: Please Help Me.

She blinked up at me. “Have you tried the train table?”

“Yes, of course.”

“Hmm.” She remained seated, looking up at me with a beleaguered expression. She was like a computer character in a video game that has exhausted its dialogue options and, therefore, its usefulness.

That’s not to say she was without pity. It was just all for herself. She was anxious for me to not be her problem.

I wanted to grab her by the arms, shouting, “This is a place meant for little children—how do you not know what to do at a time like this?!” Instead, I walked away.

One thing could no longer be ignored: Our daughter was not in the tent.

She was gone.

“I’m going to find help,” my wife said.

“Okay. I’ll stay here.” Neither saying what the other was thinking—we couldn’t lose our son too.

I stood at the edge of the tent and watched her run off. I thought about our daughter, somewhere out there without us. I imagined her clutched in a stranger’s arms. I thought about driving home with her car seat empty.

I started praying.

My wife found someone with a walkie-talkie and a clue. They radioed for help. A policeman arrived. More walkie-talkie discussions.

And then, miraculously, I saw her.

Our daughter lurked behind a barn 50 yards away on the other side of a dirt road. Clearly distraught. She was wearing a pink jacket and matching boots. No hat.

I used to run track. My specialty was sprinting. Long legs and all that. I don’t think I’ve ever run faster than I did that day.

The whole episode lasted 20 minutes. It scarred me for life.

A few years later, I watched the movie Babel. And it brought all that pain right back.

Babel came out in 2006 but I didn’t catch it until at least 2010 or 2012. It was one of those movies that ends up in your streaming queue, but you don’t remember why and are suspicious how it got there, and eventually you get bored enough to watch it.

It stars Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett as Richard and Susan Jones, an upper class couple who decide a vacation to a third world country is exactly the balm their failing marriage needs. I don’t need to tell you Pitt and Blanchett are two of the most beautiful people on Earth. You have eyes. Babel rubs dirt over all that prettiness. They’re filthy for most of the film and presumably pretty ripe. At one point, Susan admits she’s peed herself. She’d been shot and has been lingering around death’s door, but still. Gross.

Spoilers, by the way.

Babel tells an interweaving story, of which the Jones are just a part, but it all comes full circle in the end. There’s also a Moroccan family of goat herders. The youngest brother spies on his sister while she changes, with her consent, which I guess makes their deal a lo-fi version of OnlyFans. And that’s not even the most messed up storyline! That belongs to a deaf-mute Japanese teenager who spends her time trying to get pity sex from strangers because she witnessed her mother’s suicide and is now dead inside.

It’s almost as though Babel’s goal was to create the most disparate people imaginable and then conspire a way to tie them all together in order to make a statement about interconnectedness or the butterfly effect or, I don’t know, the joys of masturbating on a mountainside while goats bleat encouragement.

You may be thinking right now, “Damn, this sounds like a terrible movie.” You would be right. Babel has moments of singular power and is an affecting drama, but it’s also obsessed with making life seem both banal and perverse. But I didn’t know that when I watched it in 2010 or whenever. I just knew Pitt and Blanchett were in it, and that was enough.

I generally don’t watch horror. Slasher films are too ridiculous to take seriously. Gore porn is a major turn-off. Monster flicks are a bit of both.2 The only horror movies I enjoy are well-made paranormal films (Poltergeist, The Exorcist) or psychological thrillers (The Silence of the Lambs, The Shining). But even those aren’t movies I’ll rush out to watch, or revisit often.3

Babel is more terrifying than any horror film.

Richard and Susan leave their young children with Amelia (Adriana Barraza González), a Mexican nanny. After Richard extends their trip on account of Susan getting shot, Amelia decides to take the kids to Mexico—without the parents’ consent—so she can attend her son’s wedding.

Her dipshit nephew gives them a ride. On the way home, he decides to bust through the border because U.S. customs is harshing his mellow.4 He then strands his Aunt and the children in the middle of the desert to keep them safe, a decision only a dipshit could make in good conscience.

He promises to return but we never see him again.

Amelia and the children wander the desert aimlessly with no water or food. Desperate and facing certain death, Amelia stashes the kids under a tree and promises to come back for them. By the time she returns, they’re gone.

The kids are left to wander the desert until they die. Even more tragically, this comes after Susan is finally on the mend and it seems everything is going to be okay.

For over 10 years, that’s how I thought Babel ended. It was only when I recently rewatched it—to write this piece—that I realized that’s not what actually happened at all.

During Amelia’s interrogation by the border patrol, we’re told the children are fine and the father—e.g. Richard, aka Brad Pitt—is not pressing charges. After finishing the film, I spent the next 30 minutes googling. Was this an altered cut? Perhaps the director had walked back the original ending because he couldn’t sleep at night.

It was only after all exhausting all other avenues that I faced the truth: I’d somehow skated completely over that bit of dialogue and had created an alternate narrative. I even invented scenes that did not exist.

In my memory, the final shot was of the children wandering the bleak landscape, destined to die. Meanwhile, their parents are thousands of miles away and completely oblivious to what’s happening. They’re going to come home and discover their children are missing and presumed dead.

There’s something hideous about not realizing the shoe has already dropped. Something horrific in going about your life, blissfully unaware that it’s already ended. It’s the most tragic thing imaginable.

The one thing I remembered about Babel was something that hadn’t happened at all. I had injected myself and my own fears into the story, and came away utterly traumatized by the experience.

Here’s the funny part: I think the narrative I invented is actually better. For all of Babel’s attempts to reflect the dull realities and bizarre twists of life, it ultimately went with a happy ending.5 The conclusion I imagined, fueled by my own near-tragedy, is unforgettable.

We bought our son an unlicensed train table (the Thomas Life is not cheap) because I was tired of seeing his toys on the floor. At some point, he decided it would be a good idea to stand on the table and piss all over everything. I assume he just really wanted to amp up the drama; maybe he was farting to simulate thunder. It’s frankly the only explanation I’ll accept.

Jaws being one notable exception to this rule. It is kinda slasher-gore horror, but it’s also just a damn good movie.

In a funny twist of fate, my daughter loves horror movies. She recently went to see the original Carrie with friends and later complained it was “slow and kinda boring, and not scary at all.”

Pretty much every plot line in Babel revolves around someone doing something really stupid.

Everyone got a happy ending except the family of Moroccan goat herders. And Amelia, who ended up deported back to Mexico. So the brown people all got crapped on. I think this was the film commenting on inequality and not a bias—the writer and director are both Mexican.

I wondered why it was called "Babel", as it didn't appear to have anything to do with the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel. But, reading this, it clicked: it's about people trying to communicate with others when other people don't know what they're saying or doing, and confusion reigns.

Sheesh!! What an article! The vanishing...ugh. It's so real it's gross. Felt sick. Thank God she turned up fine!

Babel...not sure if I saw it. Maybe. Might have to watch it now (or again) because I can't quite tell if it was a bad movie or just a sad-bleh movie.