1999: When Gen X Disillusionment Had its Moment on the Big Screen

The shared themes of The Matrix, Office Space, and Fight Club

This is a free companion to this week's podcast on The Matrix.

One of the central conceits of The Matrix is that the titular VR network-cum-mind prison was modeled after the peak of human civilization, which the computers determined was a green-tinted 1999.

The idea was laughable at the time. Looking back, the machines were obviously right.

In '99, the internet was new, exciting, and uncomplicated. Back then, you "went on the internet" for a brief time and usually with a clear agenda—check email, bid on eBay, play a game. And then you went on with your life, which did not involve the internet at all.

I can't stress enough the distinction between online and the real world. There was no confusing the two, in part because there were yet no mobile devices with persistent connections. Sometimes just getting online was an exercise in patience, never mind staying connected. (Mom—your call disconnected my game of Age of Empires! Again! Arrggg!!!)

Imagine Narnia, except the portal was not a wardrobe but via a screeching 56k modem. It was that level of contrast, and also that sense of magical discovery.

Gen X Disillusionment

On the cusp of a new millennium, with this still-new internet-thing under our belts, you could argue the future seemed bright enough to require clunky blue blockers. But it didn't feel that way, because everyone agreed that the 90s sucked. It was one of the most persistent Gen X beliefs, as foundational as our trust in Jim Henson, Mr. Rodgers, and Columbia House.

Disillusionment with the American Dream is old hat these days, but Gen X was the first ones into the breach. It went unnoted at the time because a healthy suspicion of the status quo was part of our core identity.

The root of all that angst was the sense we were a few decades too late to the party.

Boomers had free love; we had HIV/AIDS. They lived in a prosperous, post-war America; we lived through recessions and in the shadow of a nuclear Cold War. They had Beatlemania; we had Wrestlemania. (I tally the last one as a Gen X win, personally.)

Gen X also lived through a seismic upheaval in the way work was done, and even the very definition of the word.

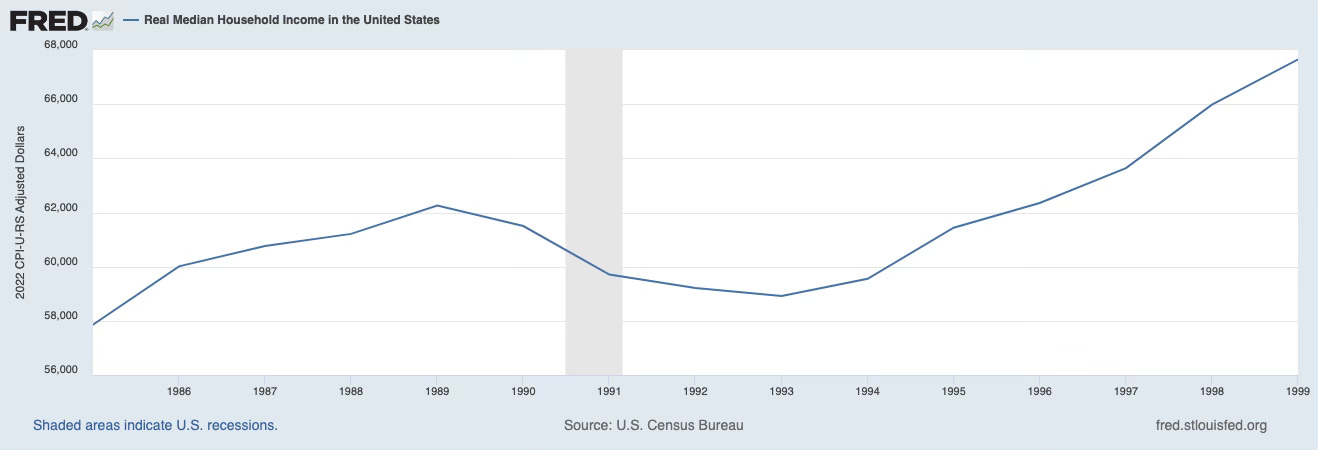

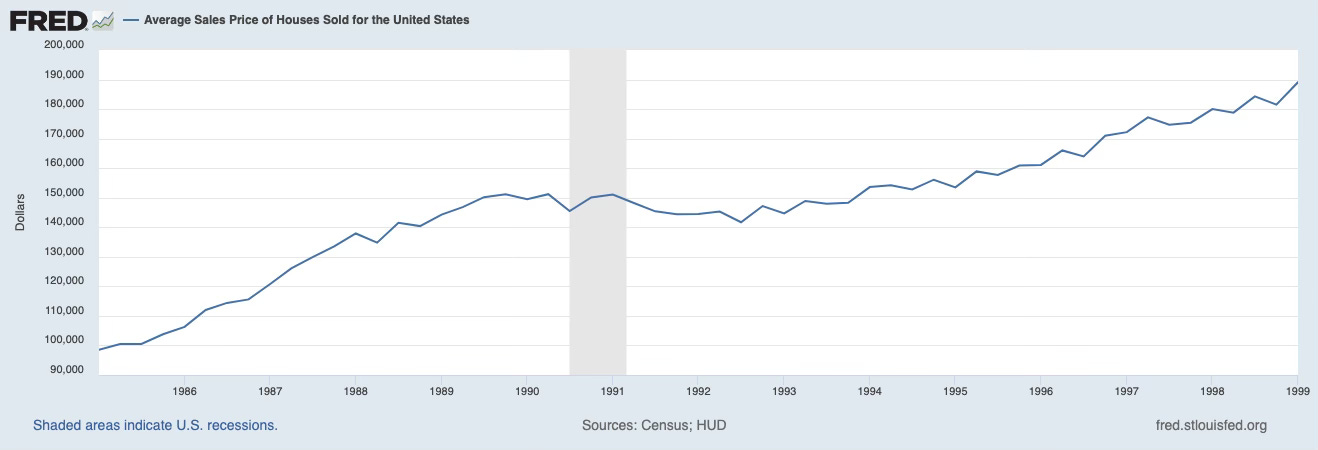

In the 80s, the number of white-collar workers surpassed their blue-collar counterparts in America for the first time. By 1990, 1 worker in 3—across all professions—was employed in a white-collar profession. This was a shift of necessity, as it was no longer possible to buy a home and raise a family on one income without a college degree; depending on the degree, even that might not be enough. Between 1985 and 1999, median US household income grew by 17%, which sounds reasonable until you realize average home prices grew by 92% over the same period.

(Ignore the impressive-looking upswing in income between 1994 and 1999; that only amounts to $8000. Housing increased by $35,000 over the same stretch.)

As for the work itself: Most white-collar jobs functionally are a lot of useless meetings, phone calls, and, increasingly, emails, the output of which creates no obvious utility or value, and certainly no physical artifacts. According to my 6th grade science class, energy can't be created or destroyed, it can only be transformed or transferred. In a white-collar profession, you pour energy into a nebulous, inanimate thing—an organism known as a corporation—which uses that energy at times and in ways that are completely divorced from your contribution. Which sounds rather like the purpose of the Matrix, come to think of it.

A future in which every day is interchangeable with the last is a slow kind of death. Suicide via Microsoft Outlook.

These are the things Gen X was grappling with at the end of the 90s.

All that angst and resentment found its way to Hollywood. In 1999, 3 major films released in which a Gen X protagonist is trapped in a soul-killing white-collar job until he finally decides to make some drastic changes.

Let's briefly tackle them, ordered by release date.

Become a paid supporter for only $3 a month!

Office Space

The comedic take that is more real than funny

To this day, Office Space remains the best representation of what working in an office is actually like. Maybe because of that, I don't find it super funny. It is very aspirational, though, in a fairy tale kind of way. Who hasn't wanted to tell the boss, "No, I don't think I'd like to do that," and then not do that thing? And suffer no consequences?

Of the three films, this is the only one that is entirely about office life. The others use the office as a springboard to propel the protagonist onto exciting adventures. Office Space doesn't flee its softly paneled walls, instead lampooning the very idea of the office as a place where anything meaningful is done, and the ridiculousness of kowtowing to a boss as though he were king. The satire trades biting commentary for plot hijinks in the third act, which is really too bad.

It's telling that the film ends with the protagonist throwing off his white collar in exchange for a blue one working construction. It's honest work, hard work, but he's happier than he's ever been. It's almost like humans weren't made to sit at a desk all day.

The Matrix

The sci-fi dystopia

Maybe I'm a masochist or something, but I've always enjoyed the scene where Neo—sorry, Mr. Anderson—is an office pleb. Something about a wasteland of gray cubicles baking under the unblinking glare of fluorescents speaks to me. I've served time in that hell.

The Matrix is just so gonzo—in all the right ways—that the sheer mundanity of the office scene stands apart almost as a set piece. The whine of the squeegee on the window. The mildly-aggrieved middle manager who probably has no real idea what his employees do, much less how they do it. The guy making photocopies who watches Neo crab-run through the maze of cubicles, and then turns back to the copier as though this was an everyday occurrence.

The office scene is the Matrix at its most bland and dehumanizing, and illustrates why Neo is so anxious to escape. Though not quite desperate enough to risk his life on a super-high window ledge; sometimes Excel ain't that bad.

Fight Club

The nihilistic drama, co-starring Brad Pitt's abs

That the office scenes in Fight Club are somehow more depressing than their counterparts in The Matrix—a film in which machines leech humans of their very everything—is a testament to Fight Club's zero-sum philosophy. Not only are offices inhuman cages, Edward Norton's job as an automotive recall coordinator hinges on his ability to take humanity out of the equation entirely.

Listen to the way he talks about his job.

"A new car built by my company leaves somewhere traveling at 60 mph. The rear differential locks up. The car crashes and burns with everyone trapped inside. Now, should we initiate a recall? Take the number of vehicles in the field, A, multiply by the probable rate of failure, B, multiply by the average out-of-court settlement, C. A times B times C equals X. If X is less than the cost of a recall, we don't do one."

He's calmly discussing a horrific scenario where people are trapped in a car and burned to death, but skipping right over all the terrible parts—not even glancing at them—to talk probabilities, which is shorthand for money. He's a ghoul. Little wonder he can't sleep, starts crashing various get-help groups, and throws in with Tyler Durden.

Much of Fight Club—apart from all that fighting—is concerned with the big question: Why? Why work a miserable job just to buy a bunch of stuff you don't really need and will one day regret having?

Fight Club directly dismantles the mystique of the American Dream, and also physically attacks its embodiment. All of that pent-up aggression finds its root in the daily drudgery of office work.

1999, 25 years Later

I find it deeply interesting that we had this brief moment at the turn of the millennium, in which these three films took different paths to arrive at the same conclusion: The office is a dehumanizing environment to be avoided at all costs.

Having worked in an office, I can't say they're entirely wrong.

There's a lot of hyperbole being thrown around, and certainly, "not all offices." But the films mine a rich lode which remains viable today.

A large portion of our identity is tied up in the work we do. If we dislike that work, or see it as without value, that naturally bleeds into our self-talk.

Cubicle farms are not conducive to maintaining the concentration necessary for deep and meaningful work, which is one reason you check email every 5 minutes. Any distraction is a micro-escape.

The Information Revolution—and its vehicle, the internet—has deemphasized the physical in favor of the digital. No matter how many spreadsheets I create, it'll never feel as impactful as mowing the lawn or cleaning the toilet. Facts.

Looking back, it's clear we had it pretty good at the time. In fact, I'd argue we had it the most-good. Think about it for a second: At the peak of our brief cultural significance, Gen X had 3 movies that all complained about how soul-sucking office work was. Yeah—paper cuts suck. But on the scale of things to complain about, the office is relatively minor. You don't need to start a fighting club or anything if work gets you down. There's like, pills for that. Easy-peasy.

1999 also saw American Beauty, which among other, grosser things, was about Kevin Spacey's growing dissatisfaction with suburbia. The suburbs are the white-collar drone's nest, and tonally American Beauty fits Gen X's generalized ennui at the time, but I'll happily push this one off on the Boomers and never think about this movie again.

9/11 abruptly ushered out this short era of cinematized dissatisfaction. There were suddenly much bigger problems to be worried about. In contrast to falling skyscrapers, the terror of terrorism, and the steady erosion of liberties in the name of peace, the quiet discontent of a monotonous office life was downright quaint, if not the height of privilege. Like many pre-9/11 things, 1999 seems like a strange artifact from a distant, unknowable past.

Even for those of us that lived it and remember.

1999 was such a great year for movies! One of the best is The Mummy, and I've probably watched that one the most out of any movie that came out that year. But also eXistenZ was released, which is probably one of the worst movies I've ever seen (and turned off because it was so bad, which I hardly ever do - I watched ALL of In The Name of the King: A Dungeon Siege Tale).

There was a great indie called Clockwatchers in this era maybe slightly earlier that was like the female Office Space in a way, it starred Lisa Kudrow and Parker Posey. Wish I could find it somewhere!